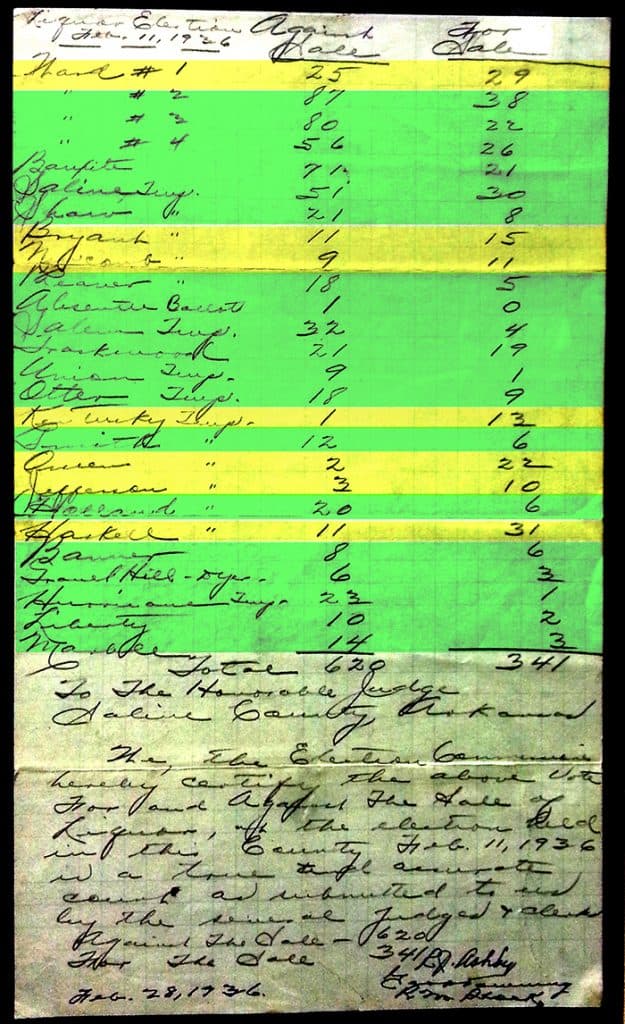

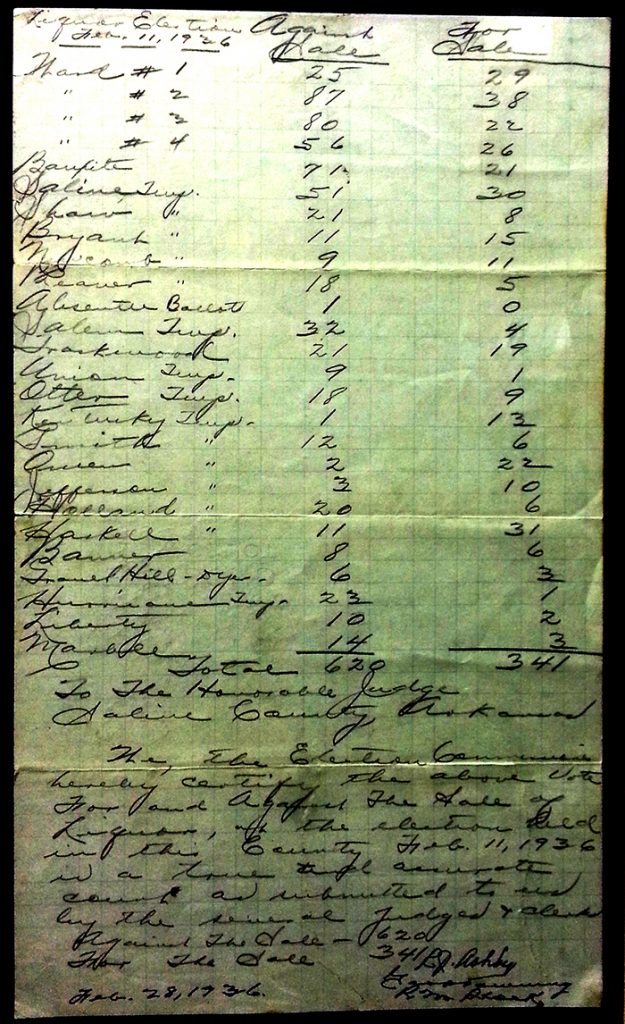

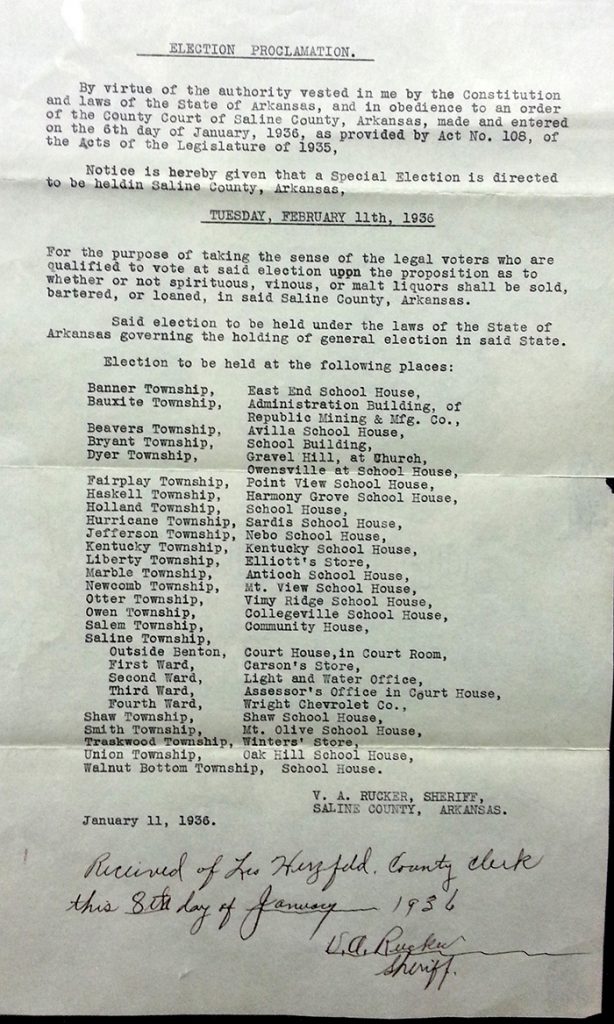

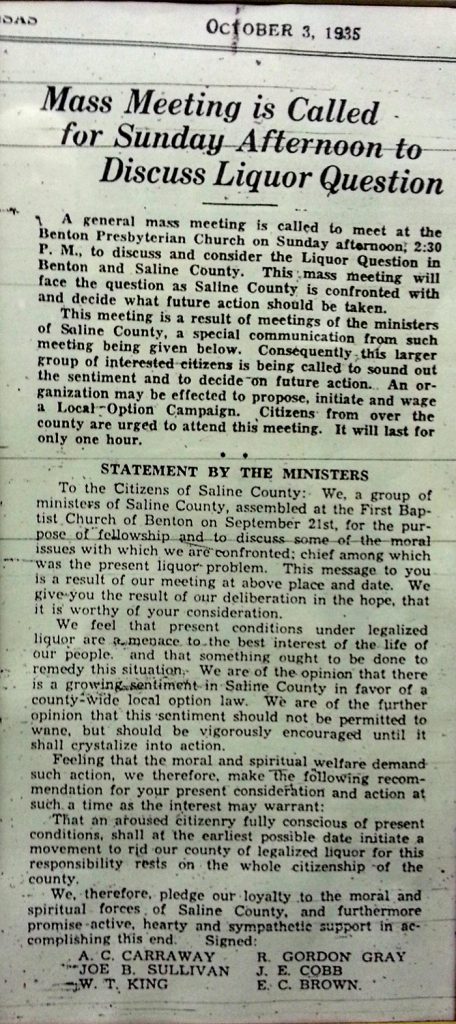

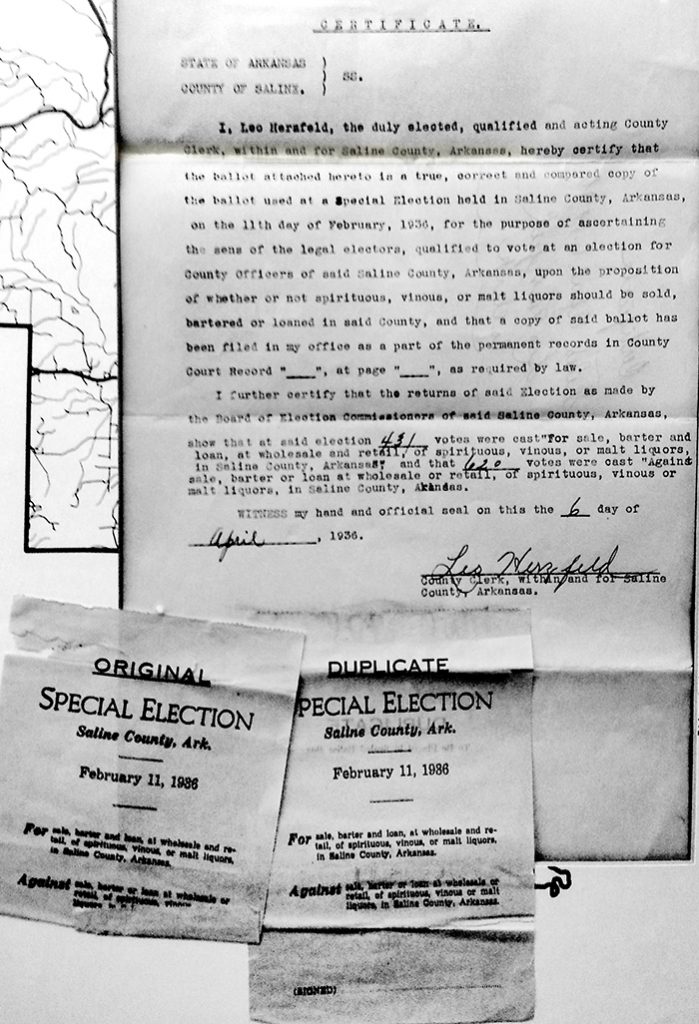

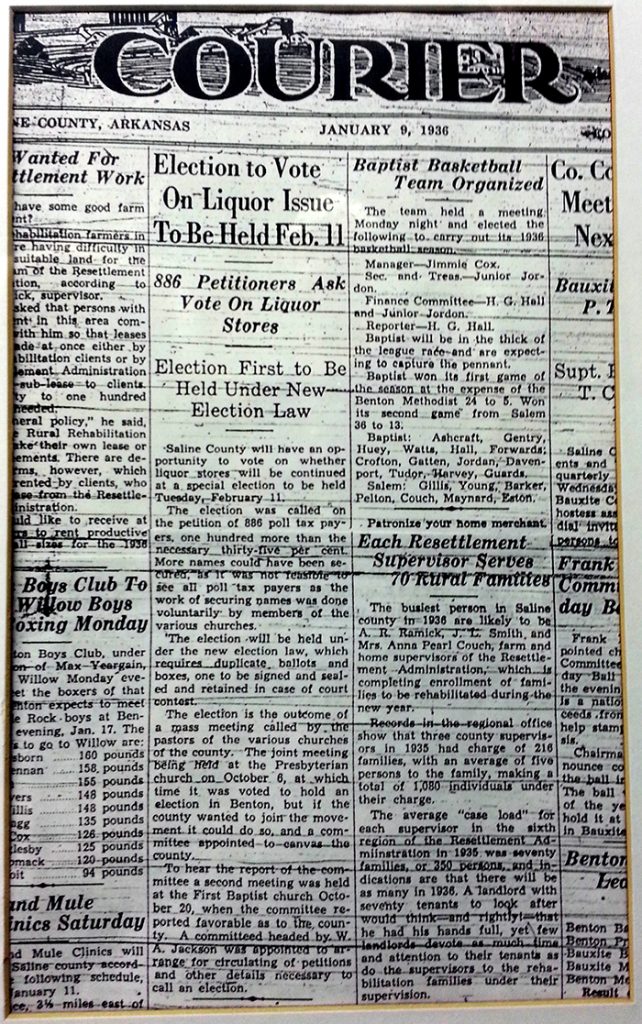

Saline County went dry after a Special Election in 1936. In October 1935, six local ministers gathered at First Baptist Church and decided to have a public meeting with the public to try to get it to a vote. The rules about getting something on a ballot must have been very different then, because it only took four months to get the vote and change the law. The following images are documents pertaining to the first meetings, the election announcement and the results.

LeeWood

It looks as if a majority of Bryant residence didn’t want to go Dry, even back then.

Jan 23, 2015

Shelli Poole

I know, this is why I highlighted the yays and nays. It’s interesting to see that the majority in certain areas wanted to stay wet. However, it was churches in Benton – the most densely populated section of the county – that led the effort to go dry. Benton is listed as Wards 1-4 in the handwritten vote count. My guess is that peer pressure had a lot to do with how a person voted.

Also note that women only got their right to vote 16 years earlier, and I’ll bet very few did still, due to their husband or father’s wishes. I don’t have the benefit of knowing the statistics regarding the percentage of voters who actually voted, and who was what gender – or race, for that matter. Minorities had the right to vote for a long time (since 1870), but it wasn’t until 1965 (29 years after this particular election) that the Voting Rights Act closed lots of loopholes that kept African Americans and others from voting. And the probable lack of accountability in election tallies is a whole other can of worms. But… it’s all moot regarding this issue, since here we are in wet county again.

Jan 23, 2015