See the photos and read the events of the case, the reasoning in the appeal, and the Arkansas Supreme Court’s official opinion verbatim below. ??

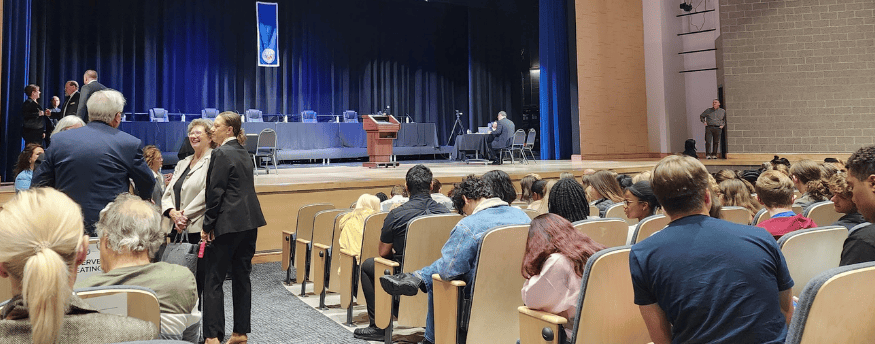

If you attended the “Appeals on Wheels” murder trial appeal event at the Bryant High School Fine Arts Center on October 19, 2023, you’re probably wondering about the outcome. If you didn’t attend, let’s start will some background… The Arkansas Supreme Court Justices host an event twice a year where they get out of the courtroom and take an appeal on the road. The venue is usually a school or university.

This most recent appeal heard in Bryant, was an oral argument concerning an appeal by Hunter Bishop. He was convicted of the murder of Maddison Clevenger. Mr. Bishop appealed on the basis of his belief that an officer did not follow procedure while arresting him.

The question at this appeal was not whether he was guilty, but whether the Searcy Police Department’s Officer John Aska overstepped his boundaries. If so, the trial would need to happen all over again.

Read the case narrative below, along with the description of the argument from appellant and appellee attorneys, along with the result.

Cite as 2023 Ark. 150

SUPREME COURT OF ARKANSAS

No. CR-22-651

HUNTER BISHOP, APPELLANT

V. STATE OF ARKANSAS, APPELLEE

Opinion Delivered: October 26, 2023

APPEAL FROM THE

WHITE COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

[NO. 73CR-20-296]

HONORABLE MARK PATE, JUDGE

AFFIRMED.

COURTNEY RAE HUDSON, Associate Justice

THE INTRO

Appellant, Hunter Bishop, appeals his capital-murder conviction in the White County Circuit Court. He was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. For reversal, Bishop argues that the circuit court erred by

(1) denying his motions to suppress evidence from the traffic stop,

(2) denying his motions to suppress evidence from his detention and arrest, and

(3) permitting the State to introduce videos containing statements made by law enforcement officers.

We affirm.

THE CASE

On May 22, 2020, the State filed a criminal information charging Bishop with the capital murder of Maddison Clevenger, in violation of Arkansas Code Annotated section 5-10-101(a)(4) (Supp. 2019). Bishop’s jury trial was held March 7–11 and 14–18, 2022. Evidence introduced at trial showed that Maddison had uncharacteristically not reported for work on May 15, 2020.

A group of people including her father, a coworker, and Frances Ballek of the Searcy Police Department had gathered at Maddison’s house at about 8:30 a.m. that day to check on her. No one answered a knock on the door, and a dog could be heard barking inside. The doors were locked, but Maddison’s father pushed an air conditioner unit out of a window, climbed into the house, and opened the front door. Maddison was found dead inside. There was no sign of forced entry, and the house had not been ransacked. However, the 9mm Glock 48 handgun that Maddison had purchased four days earlier could not be found.

Later that day, officer John Aska of the Searcy Police Department was on patrol when he was advised by criminal investigators that they wanted to speak with Bishop. Authorities did not have precise contact information for Bishop, so they advised Aska to look for his vehicle. Aska waited in the vicinity of Bishop’s residence. At approximately 2:45 p.m., Aska spotted Bishop’s maroon Chrysler 300 drive by and conducted an investigatory traffic stop. Aska ordered Bishop out of the car and, during a pat-down search, discovered an empty holster. Aska asked Bishop where the gun was, but Bishop denied having a gun. Bishop was handcuffed, transported to the Searcy Police Department, and interviewed after he received his Miranda warnings. Bishop gave statements denying any involvement in the murder.

Police performed an inventory search of Bishop’s vehicle at the scene of the stop and discovered Maddison’s handgun wedged between the driver’s seat and center console. Although police obtained a warrant, the vehicle search was conducted before the warrant was issued. An autopsy revealed that Maddison had been shot once in the back of the head with a 9mm bullet. An expert testified that the bullet that killed Maddison was fired from her handgun.

Before the trial, Bishop filed four motions challenging the traffic stop and subsequent detention and arrest as being a violation of Arkansas law and the U.S. Constitution. Bishop argued in those motions that all evidence found in connection with the stop and detention and arrest should be suppressed. The circuit court held a suppression hearing that included testimony from investigating detectives and Aska.

At the hearing, investigators testified that before Aska stopped Bishop, they had learned that the bullet recovered at the scene was likely a 9mm round, that Maddison was in a relationship with Bishop, that Bishop was a convicted felon, that Bishop had accompanied her to purchase her Glock several days earlier, and that Maddison’s gun was not found at her home or in her car. They had also been given a description of a vehicle seen in the area at the time a gunshot was heard, but it did not match Bishop’s vehicle.

Additionally, investigators had developed two other persons of interest. One was Charles Stacy, Maddison’s former husband, and the other was Andrew Skinner, who is the former boyfriend of Maddison’s sister. Skinner was believed to have had a key to Maddison’s house. He had also previously threatened to harm Maddison and had stolen her dog. Aska testified that on May 15, he was informed “through word of mouth” that investigators were looking for Bishop. Aska said he was also told that Bishop was considered armed and dangerous and was a convicted felon.

On February 15, 2022, the circuit court entered a written order denying Bishop’s motions. The circuit court ruled that Bishop was legally “stopped, seized, and arrested.” The circuit court concluded that there was “reasonable suspicion to stop and probable cause to arrest [Bishop] based on the officer’s observations, knowledge of before, and that the holster was empty.”

The circuit court also ruled that Bishop’s statements were properly obtained and partially denied his motions to suppress video of his interviews. The circuit court entered an amended order denying the motions on April 1, 2022.

The jury convicted Bishop of capital murder and sentenced him to life imprisonment without parole. The State nolle prossed a charge of possession of a firearm by certain persons. Bishop filed a timely appeal.

THE APPEAL

We turn now to Bishop’s appeal. In two related points, Bishop first argues that his motions to suppress evidence found during the traffic stop and his motion for reconsideration should have been granted because the traffic stop was not authorized under the Arkansas Rules of Criminal Procedure or the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

In reviewing the denial of a motion to suppress evidence, this court conducts a de novo review based on the totality of the circumstances, reviewing findings of historical facts for clear error and determining whether those facts give rise to reasonable suspicion or probable cause, giving due weight to inferences drawn by the circuit court. Lewis v. State, 2023 Ark. 12. A finding is clearly erroneous, even if there is evidence to support it, when the appellate court, after review of the entire evidence, is left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been made.

Id. We defer to the superiority of the circuit court to evaluate the credibility of witnesses who testify at a suppression hearing. Dortch v. State, 2018 Ark. 135, 544 S.W.3d 135. A circuit court’s ruling will be reversed only if it is clearly against the preponderance of the evidence. Cone v. State, 2022 Ark. 201, 654 S.W.3d 648. Additionally, we will affirm the circuit court’s decision when it reached the right result, even if it did so for the wrong reason. Hartley v. State, 2022 Ark. 197 n.3, 654 S.W.3d 802 n.3.

The standards for determining whether the traffic stop was authorized are the same under both our rules of criminal procedure and the United States Constitution. 1

Rule 3.1 of the Arkansas Rules of Criminal Procedure provides:

A law enforcement officer lawfully present in any place may, in the performance of his duties, stop and detain any person who he reasonably suspects is committing, has committed, or is about to commit (1) a felony, or (2) a misdemeanor involving danger of forcible injury to persons or of appropriation of or damage to property, if such action is reasonably necessary either to obtain or verify the identification of the person or to determine the lawfulness of his conduct. An officer acting under this rule may require the person to remain in or near such place in the officer’s presence for a period of not more than fifteen (15) minutes or for such time as is reasonable under the circumstances. At the end of such period the person detained shall be released without further restraint, or arrested and charged with an offense.

1 The circuit court analyzed the stop as an arrest and said it was “not a [Terry] stop or 3.1.” The order is not entirely clear as to whether the circuit court believed the encounter was an arrest from the outset, or progressed to an arrest after the holster was found. Regardless, we can affirm the circuit court when it reached the right result for the wrong reason. See Hartley, 2022 Ark. 197 n.3, 654 S.W.3d 802 n.3.

Ark. R. Crim. P. 3.1 (2020).

Rule 2.1 defines reasonable suspicion as

a suspicion based on facts or circumstances which of themselves do not give rise to the probable cause requisite to justify a lawful arrest, but which give rise to more than a bare suspicion; that is, a suspicion that is reasonable as opposed to an imaginary or purely conjectural suspicion.

Ark. R. Crim. P. 2.1 (2020).

Similarly, a police officer may conduct an investigatory stop of a person without violating the Fourth Amendment if the officer has “a reasonable suspicion that ‘criminal activity may be afoot.’” Laime v. State, 347 Ark. 142, 156, 60 S.W.3d 464, 474 (2001) (quoting Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 30 (1968)); see also Shay v. State, 2018 Ark. 393, 562 S.W.3d 832 (stating that the purpose of Rules 3.1 and 3.4 is to give effect to the holding in Terry). Reasonable suspicion exists when the officer has “a particularized and objective basis for suspecting the particular person stopped of criminal activity.” Kansas v. Glover, 140 S. Ct. 1183, 1187 (2020) (citations and quotations omitted). It is more than a mere hunch, but less than probable cause, and considerably less than a preponderance of the evidence.

Id. Determining the existence of reasonable suspicion is a commonsense task depending on “the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act.” Navarette v. California, 572 U.S. 393, 401 (2014) (citations and quotations omitted).

Reasonable suspicion is a totality-of-the-circumstances analysis where the individual facts known to law enforcement, and the reasonable inferences that follow from them, are not taken in isolation, but considered as a whole. E.g., United States v. Arvizu, 534 U.S. 266 (2002). The collective knowledge of law enforcement at the time of the stop is to be considered in the evaluation of whether reasonable suspicion exists. United States v. Hensley, 469 U.S. 221 (1985).

In this instance, before Aska initiated the traffic stop, police collectively knew that Maddison had been murdered with what appeared to be a 9mm firearm, that Bishop had accompanied Maddison to the store when she purchased a 9mm handgun earlier in the week, that the gun was not found at Maddison’s home or in her car, and that a neighbor heard a gunshot in the early morning hours of May 15. They also knew that there were no signs of forced entry into Maddison’s home, that Bishop was in a relationship with Maddison, and that Bishop had a previous felony conviction and was forbidden from owning or possessing firearms. 2

2 At oral argument the State contended that authorities knew before the stop that Bishop had been seen on video holding a firearm when Maddison purchased her Glock. However, the record is not clear as to when that video was obtained, and we do not consider it in our reasonable suspicion analysis.

Although there were other persons of interest, and Bishop’s car did not match a description of one seen in the area, the facts collectively known to law enforcement provide reasonable suspicion that Bishop was a felon in possession of a firearm, and that he committed Maddison’s murder. Because reasonable suspicion is the standard under both Rule 3.1 and the Fourth Amendment, the stop was not improper under either, and suppression of the evidence obtained after the stop is not warranted on these points.

In his next two related points, Bishop asserts that his motions to suppress and for reconsideration should have been granted because his detention was not authorized by the Arkansas Rules of Criminal Procedure or the Fourth Amendment. Pursuant to Rule 4.1, a law enforcement officer may arrest a person without a warrant if “the officer has reasonable cause to believe that such person has committed a felony.” Ark. R. Crim. P. 4.1(a)(1) (2020).

The Fourth Amendment prohibits a warrantless arrest without probable cause. Joseph v. Allen, 712 F.3d 1222 (8th Cir. 2013). Most courts agree that there is no difference in the terms “reasonable cause” and “probable cause.” McGuire v. State, 265 Ark. 621, 580 S.W.2d 198 (1979).

Probable cause to arrest without a warrant exists when the facts and circumstances within the collective knowledge of the officers and of which they have reasonably trustworthy information are sufficient in themselves to warrant a person of reasonable caution in the belief that an offense has been committed by the person to be arrested. Friar v. State, 2016 Ark. 245. Such probable cause does not require that degree of proof sufficient to sustain a conviction; however, a mere suspicion or even “a strong reason to suspect” will not suffice. Roderick v. State, 288 Ark. 360, 363, 705 S.W.2d 433, 435 (1986) (quoting Henry v. United States, 361 U.S. 98 (1959)).

The assessment of probable cause is based on factual and practical considerations of prudent individuals rather than the discernment of legal technicians. Id. It is based on the officers’ knowledge at the moment of the arrest. Friend v. State, 315 Ark. 143, 865 S.W.2d 277 (1993). The determination of probable cause is also measured by the facts of each particular case. Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963).

In this instance, as discussed above, police had a reasonable suspicion that Bishop was a felon in possession of a firearm and had committed Maddison’s murder. Therefore, his initial stop and detention was authorized under the Fourth Amendment and Rule 3.1. During that stop, Aska conducted a pat-down search. Rule 3.4 of the Arkansas Rules of Criminal Procedure provides that

[i]f a law enforcement officer who has detained a person under Rule 3.1 reasonably suspects that the person is armed and presently dangerous to the officer or others, the officer or someone designated by him may search the outer clothing of such person and the immediate surroundings for, and seize, any weapon or other dangerous thing which may be used against the officer or others. In no event shall this search be more extensive than is reasonably necessary to ensure the safety of the officer or others.

Ark. R. Crim. P. 3.4 (2020).

Similarly, the Fourth Amendment allows for a search for weapons for the protection of a police officer, when the officer “has reason to believe that he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual, regardless of whether he had probable cause to arrest the individual for a crime.” Terry, 392 U.S. at 27; see also Davis v. State, 351 Ark. 406, 94 S.W.3d 892 (2003) (observing that Terry is consistent with Rule 3.4 and authorizes a pat-down search when a reasonably prudent person in the circumstances would be concerned about his or her own safety or the safety of others).

In this case, the same facts that provided reasonable suspicion for the initial stop provided reasonable suspicion for the pat-down search. Police collectively knew that Bishop was wanted for questioning in connection with a murder, and Aska was advised to try to stop him. Aska testified that he had been told that Bishop should be considered armed and dangerous.

Aska’s search therefore was a practical and prudent endeavor based on his knowledge of the facts. As Aska performed the pat-down search, he discovered the empty holster. This discovery then provided probable cause to arrest Bishop. In fact, Bishop does not challenge his detention after the holster was discovered. Accordingly, the circuit court’s order denying suppression was not clearly against the preponderance of the evidence.

Bishop’s final argument is that the circuit court abused its discretion when it allowed the jury to see videotaped custodial interviews that included statements from investigators. Two videotaped interviews were played for the jury. The circuit court issued the following admonition prior to testimony offered by Detective Smith:

Nothing said by law enforcement in the interrogation should be considered by you as factually true. You should also not consider the accusations, insinuations, or the tone of law enforcement to influence you in your determination of Hunter Bishop’s guilt or innocence. Portions of the following video are muted. In deciding this issue or the issues, you should consider the testimony of the witnesses and the exhibits received into evidence. The introduction of evidence in Court is governed by law. You should accept, without question, my rulings as to the admissibility or rejection of evidence drawing no inferences that by these rulings I have in any manner indicated my views on the merits of the case.

The second video was played in conjunction with Detective Brian Fritts’s testimony. The circuit court read what was essentially the same admonition before Fritts testified.

Before the trial, Bishop filed a motion in limine seeking to exclude any portions of the interviews wherein law enforcement officers suggested that he was lying, insinuated that he was guilty of murder, or discussed his status and prison sentence as a felon. Bishop also argued that any probative value of these statements was outweighed by unfair prejudice.

The circuit court granted the motion in part and denied it in part. The circuit court ruled that any references to Bishop’s felony convictions were inadmissible, but it concluded that playing only Bishop’s responses to questions would be confusing. Therefore, the circuit court allowed the videotaped interviews to include most statements made by investigators but ruled that there could be no references to Bishop’s criminal record.

Circuit courts have broad discretion on evidentiary issues, and we will not reverse a circuit court’s ruling on the admission of evidence in the absence of an abuse of discretion. Collins v. State, 2019 Ark. 110, 571 S.W.3d 469. An abuse of discretion is a high threshold that does not simply require error in the circuit court’s decision, but requires that the circuit court act improvidently, thoughtlessly, or without due consideration.

Id. Furthermore, we will not reverse unless the appellant demonstrates that he was prejudiced by the evidentiary ruling. Edison v. State, 2015 Ark. 376, 472 S.W.3d 474. Additionally, the issuance of a limiting instruction may remove the inflammatory effect of evidence. Kilpatrick v. State, 322 Ark. 728, 912 S.W.2d 917 (1995).

Bishop’s argument here is grounded in Rules 403 and 404 of the Arkansas Rules of Evidence. Pursuant to Rule 403, relevant evidence may be excluded “if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading of the jury[.]” Rule 404 provides that evidence of a person’s character is generally not admissible.

In this instance, the record demonstrates that the circuit court considered the parties’ arguments and granted Bishop’s motion in part and denied it in part. The circuit court determined that it could not eliminate all of the investigators’ comments because it would confuse the jury. However, it concluded that references to Bishop’s prior felonies would not be allowed. Additionally, the circuit court issued an admonition before the videos were played. Thus, the circuit court did not act improvidently, thoughtlessly, or without due consideration in making its ruling. Accordingly, it did not abuse its discretion, and it did not commit reversible error on this point. 3

3 Bishop argues in his brief that the jury heard references to his prior felony conviction and prison sentence. He specifically cites several places in the record where the transcription of the videos played for the jury refers to the conviction or sentence. However, if the references to Bishop’s felony and prison sentence were heard by the jury, it would not establish an abuse of discretion because the admission of those references would have been in violation of the circuit court’s order.

THE REVIEW

Rule 4-3(a) Review

Because Bishop received a life sentence, the record has been examined for all objections, motions, and requests made by either party that were decided adversely to him in compliance with Arkansas Supreme Court Rule 4-3(a) (2022), and no prejudicial error has been found.

Affirmed.

Short Law Firm, by: Lee D. Short, for appellant.

Tim Griffin, Att’y Gen., by: Christian Harris, Sr. Ass’t Att’y Gen., for appellee. https://opinions.arcourts.gov/ark/supremecourt/en/item/522206/index.do